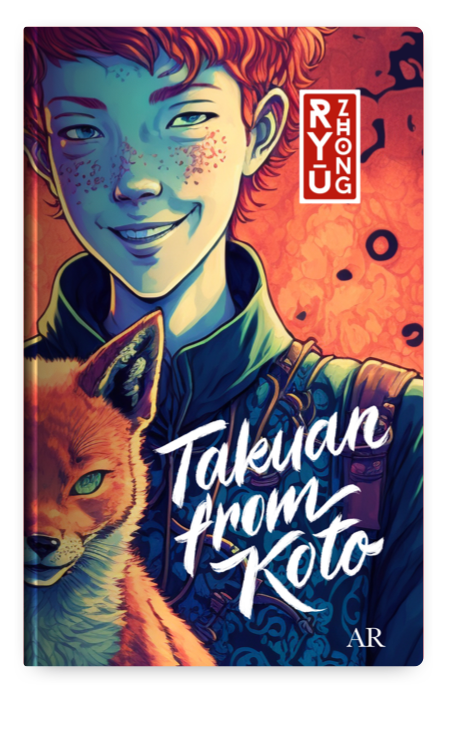

Some time ago, in a village of Koto which stood exactly on the border of the principality of the Four Rivers and the province of Brocade Mountain, a baby was born.

He (for he was a boy) was almost completely unremarkable – but there was a special, mischievous kind of cunning in his eyes that set him apart. His mother named him Hatsukoi, which means ‘fruit of my love’ in the local tongue. The boy grew up quickly, and his love for all sorts of tricks and pranks grew even faster than he did. A couple of years later, a sister was born in his family, who also turned out to be overly curious, but far less so than Hatsukoi.

When the boy reached the age of twelve, he was put to work with his father in the forge. He quickly got tired of the monotonous work, and thus began to look for other ways to entertain himself.

One day, Hatsukoi left his home and departed from the village in search of adventure. Not having gone far, he came to a deep well. It was made of logs, and was located under a high canopy that protected it from both the hot summer sun and the heavy seasonal rains. Hatsukoi climbed upon the well’s roof and looked ahead.

A small cloud of dust appeared on the horizon; riders were galloping towards Hatsukoi. The boy instantly recognised that the riders were wealthy people, for horses were not cheap, and they rarely appeared in Hatsukoi’s home village. Eager to practise his fondness for tricks on these rich strangers, he began to figure out how to outwit them.

The riders soon reached the well. There were seven of them: a local governor named Tu Fang; his half-brother, Tu Liwei; and five hunters. The brothers had been out falconing that day, but they had failed to catch anything, which had left them in a particularly foul mood – much like that of a toad on a dry day.

Governor Tu Fang was the first to notice Hatsukoi, who was lying on the roof of the well with his head hanging down.

“What are you doing there?” he asked.

Hatsukoi shrugged his shoulders. “I’m looking to see if the well has a bottom.”

Tu Fang frowned at the boy’s response. Why would someone need to look for the bottom of a well? It sounded very suspicious to him.

“Well, get down!” he barked.

“No,” Hatsukoi answered.

“Get down by your own will, or my hunters will shoot you with their arrows.”

Hatsukoi slowly climbed down. Tu Fang waved to one of his hunters, who immediately grabbed the boy by the scruff of his neck.

“Ai! What are you doing?!” yelled Hatsukoi, struggling, but the hunter held him tightly.

“Tell me at once,” demanded Tu Fang, “what is in this well, and then perhaps I’ll let you go.”

Hatsukoi trembled like bamboo in a strong wind. He began, “I have seen—”

“What did you see?” Tu Fang interrupted impatiently.

“I saw a thief hide his bounty here.”

“Bounty?” Tu Fang exchanged glances with his brother.

It must be said that unselfish people rarely went on to become governors. Tu Fang was no exception. He thought only of ways to feed his insatiable greed. And Tu Liwei, being his half-brother, was a pea from the same pod. So, at that moment, the brothers came up with the same thought.

And Hatsukoi was counting on it.

“A whole bag filled with all kinds of stuff,” he said confidently. “Gold, jewels, pearls… If you look from the roof, you can see how it glitters at the bottom.”

Tu Fang dismounted, went to the well and looked inside. Water was splashing somewhere far below, but it was too dark to see anything at all.

“You lie!” he exclaimed. “Nothing glitters down there.”

“I’m not lying, sir, I swear! It’s because of the roof – it blocks the light. From above, everything is perfectly visible.”

Tu Fang thought about this. “Well, then,” he reasoned, “since this well stands within the boundaries of lands belonging to the duke of the Four Rivers, and since I am his governor here, that means that everything in this well belongs to me. Isn’t that right, brother Liwei?”

“But we found the well together, brother Fang,” Tu Liwei answered.

Tu Fang understood that he would have to share the bounty, but that was a small price to pay for the treasures that might lie inside the well. So, he called out to the hunters: “Bring me a rope!”

The hunters unwound a long rope and tied it to one of the wooden posts that held up the roof. They then allowed the loose end to dangle down into the darkness of the well.

Tu Fang turned to Hatsukoi. “Climb down, boy,” he commanded, “and bring me the thief’s spoils.”

This was the instruction that Hatsukoi had been waiting for. Released by the hunter who had been restraining him, he climbed onto the well and used the rope to slide down into the damp darkness. After a moment, he fell silent.

“Well?” the governor called to him.

“The rope is too short,” Hatsukoi called from the well. “Is there a longer one?”

The hunters brought a second rope, but it, too, was of inadequate length.

Tu Liwei scratched his head. “What are we going to do?”

“Ride to the castle for a rope!” his brother commanded.

“Should we send the hunters?”

“Take them, but come back alone,” said Tu Fang in a low, quiet voice. “I will guard the boy so that he does not escape.”

Tu Liwei understood his brother perfectly. It was the law that of every treasure found, half had to be put into the state coffers of the Four Rivers. “And who knows how much gold there is at the bottom of the well?” Tu Liwei thought to himself. “Better if only my brother and I see it, and then there will be no need to share it with anyone else.”

Tu Liwei nodded at his brother, shouted at the hunters and then rushed with them to the castle at full speed.

Tu Fang remained at the well. He peered down inside it and called: “Are you still there, boy?”

“I am, sir!” Hatsukoi answered him. “Are you left alone? Has everyone gone?”

Tu Fang felt so confident that this boy could do him no harm, that he confessed: “Yes, there is no one else here.”

“I cheated, sir,” called Hatsukoi. “The rope is exactly enough. I have reached the bag.”

“You have the treasure?” Tu Fang exclaimed. “You tricked me!”

“No, sir,” Hatsukoi replied. “I waited for the others to leave, so that you can keep it for yourself. The bag is so heavy, sir!”

Tu Fang was surprised. “And for what reason did you plot this?”

“I was hoping you would give me a single trinket from the loot, sir.”

The governor grinned, for Hatsukoi reminded him of himself at a younger age. “Here’s a scoundrel!” he thought, and then he began plotting himself, as to how he would avoid the suspicions of his brother.

“Alright, young scoundrel – bring up the bag!”

“I can’t; it’s too heavy,” came Hatsukoi’s voice from the well.

“Tie it to the rope!”

“I can’t even move it, sir! It’s stuck in the wall!”

“Alright,” the governor grumbled. “Get yourself out, then.”

In less than a minute, a red-haired head appeared from the well, and then the whole of Hatsukoi, whose clothes were soaked through.

“You stand watch,” Tu Fang barked. “I’ll climb down myself.”

He climbed onto the curb of the well and grabbed the rope with his hands.

“Wait a moment, sir!” Hatsukoi called. “The water in the well is very dirty. Surely you don’t want to ruin your beautiful clothes?”

Tu Fang knew that the boy was right: his clothes were beautiful, and expensive, too; he certainly didn’t want to ruin them, so he began to hastily undress.

Off came his robes with golden embroidery, his silk shirt, and his fur-lined leather boots. He even took off his necklace with silver and jewels, until finally, Tu Fang was left only in his underwear. He again climbed onto the well curb and slid down the rope.

The well was not at all as deep as Hatsukoi had portrayed it to be, and it was not long before the governor plopped into the dirty water. Spitting, he grabbed the rope with one hand, and with the other began to feel the walls of the well in search of the bag.

He could find nothing.

“Damn boy!” the governor shouted when he realised Hatsukoi’s deceit. “Wait until I get out of here – I’ll teach you a good lesson!”

With these words, Tu Fang began to climb up. But just as he lifted himself, the rope became slack and dropped down, and the governor was sent splashing back into the muddy waters, cursing.

Hatsukoi had not wanted the governor to teach him a lesson, however good it might be – so he had untied the rope.

With Tu Fang stuck in the well, Hatsukoi neatly tucked the governor’s rich clothes and jewellery into a travel bag strapped to his horse, and then, he deftly jumped into the saddle.

“Hey-gey!” shouted Hatsukoi.

Startled, the horse gave such power to the gallop that the boy was lifted into the air, along with the saddle, at every jump. Within five minutes, Hatsukoi regretted being on a horse’s back at all.

But he couldn’t stay at the well any longer. The governor’s half-brother was already in the castle, where he had let the hunters go, grabbed a longer rope and galloped back.

By the time Tu Liwei returned to the well, Hatsukoi was already far away. The horse had finally calmed down, and the boy rode along the road, swaying in the saddle.

Hatsukoi pondered what to do with his rich bounty. He did not need a horse or any expensive clothes. In his home village, it was not at all worth appearing with them. But he didn’t worry needlessly. He changed into the governor’s clothes, pulled up the belt and rolled up the sleeves. He found a coloured scarf in the pocket and tied it around his head. On an expensive horse and in expensive clothes, he now looked no worse than a governor’s spoiled relative.

After a little while, travelling merchants came across Hatsukoi. Their carts were heavily loaded, and hired guards rode nearby.

“Where have you come from?” Hatsukoi asked.

The merchants named the city in which Tu Fang’s castle stood.

“This is exactly what I need,” thought Hatsukoi gleefully, “to teach that greedy Tu Fang one more lesson.” And he said to the merchants: “Hold your horses, my good sirs. I was sent by Governor Tu Fang, to whom I am nephew. He told me to pick up the most beautiful carpet I could find and bring it to the castle.”

The merchants were only too glad to show Hatsukoi their wares, especially after hearing of his high connections. Hatsukoi looked down upon the wagon loaded with colourful carpets, feigning a convincing interest in their quality, before selecting the largest one he could find.

“This one,” he said with certainty.

“This one is seven gold pieces, sir,” the merchant said quickly. The true value of the carpet was three gold pieces at best, but the merchant had been engaged in commerce all his life for a reason: he realised that the arrogant youth did not understand anything about carpets, and certainly would not recognise that the largest one was not the most beautiful, nor the most valuable.

“Deal!” Hatsukoi said, and began to fumble in his pockets. Then he cried: “That’s bad luck! The governor gave me only five. Seven gold pieces exactly, say you?”

“I’m ready to settle for six if you pay now,” ventured the merchant, whose eyes had begun to glitter at the thought of his extensive profit.

“Write a note for me, good sir,” Hatsukoi said. “And I’ll persuade the governor somehow.”

The greedy merchant immediately wrote out an invoice, indicating that the best carpet had been chosen for him, and that only out of respect for the governor was he ready to give up so much on its price. He then stamped a ring imprint on a piece of paper, certifying the deal.

“Back in a moment!” Hatsukoi shouted, and gave his horse a good slap.

The merchant stopped the convoy and began to wait for the return of this rich young delegate. Satisfied with the deal, he took a skin of wine from his riding bag and enjoyed a good sip of it.

Before the trader emptied the wineskin, Hatsukoi had already entered Tu Fang’s castle.

The governor himself was not in the castle, just as his brother was not either. Both were still at the well. Tu Fang told Tu Liwei of the wrong that the boy had done to him, but Tu Liwei only grinned inwardly – it was clear that his brother Fang had paid the price for his greed.

“You should have waited for me and not climbed into the well!” he chastised.

“I didn’t want to waste time,” Tu Fang argued, but Tu Liwei cared nothing for these excuses; he was already considering how he would make fun of his brother upon their return to the castle.

“Let’s hurry!” Tu Fang urged him. He did not at all want to show himself to his relatives and servants in his underwear.

“But can we even catch up with him, two people on one horse?” parried Tu Liwei.

“Then you go, and I’ll wait here and dry up.”

“No, I won’t leave you. I’ll take you to the castle first.”

“But the boy will be gone!”

“Wherever he goes, someone is bound to recognise your horse and raise the alarm. Let’s go to the castle!”

Thus they argued, to Hatsukoi’s advantage, Tu Fang unwilling to admit that he was ashamed to appear in the castle, and Tu Liwei determined to ridicule him in front of their relatives.

Hatsukoi, meanwhile, did not hesitate. He proceeded to the house of the treasurer with utmost haste. Once there, he knocked upon the lintel, and only then did he dismount – so that the treasurer could see whose horse Hatsukoi had arrived on.

Just before entering the castle, the boy changed clothes again. He took off his expensive clothes and hid them in the bushes just in case, leaving only a scarf, and introduced himself to the treasurer as an ordinary messenger.

“The governor sent me on an errand!” he blurted out. “Here’s the receipt.”

The treasurer looked at the extended letter and noticed the seal – and then he squinted at Hatsukoi.

“Did the governor himself send you?”

“Here’s his handkerchief,” Hatsukoi said. “As confirmation.”

The treasurer nodded and handed the boy a heavy purse in which six gold pieces jingled.

“Keep the handkerchief and the note for yourself,” said Hatsukoi, quite pleased, “to remind the governor in the event that he forgets about the errand.”

The treasurer was well aware of the forgetfulness of Tu Fang, who used every opportunity to squeeze more money out of the peasants and the officials subject to him. Remembering this, he was convinced of the sincerity of the messenger and, with a light heart, returned to his business.

Hatsukoi led the horse towards the exit of the castle.

At that very moment, one of the hunters was walking from the stable to the dining room. He noticed Hatsukoi and shouted: “Has the governor returned?”

“Not yet,” Hatsukoi replied, and spurred his horse on.

But the hunter had already identified the thoroughbred horse of the governor and suspected something was wrong. He cried out: “Hey, stop!”

Hatsukoi only gripped the horse’s flanks tighter.

The hunter hurried to the stable, jumped on his horse and rushed off in pursuit. He could not catch up with Hatsukoi as the governor’s horse was too lively, but he did not leave the chase.

Hatsukoi noticed this, although not immediately. He managed to get ahead, and the hunter on his horse became no larger than a gadfly; but he didn’t lag behind.

Luckily for Hatsukoi, there was a large river ahead – one of the four that the principality was named after. There was a small house near the river where a fisherman lived.

Hatsukoi reined in his horse just outside the house, kicking up a cloud of dust. The fisherman appeared at the noise. He asked, wincing: “What are you dusting?”

“I’m in a hurry,” Hatsukoi replied. “I need to get to the village as soon as possible.”

He named a village that was on the other side of the river and downstream. The fisherman looked the boy up and down, and then turned his gaze upon the horse. He had no way of knowing, of course, that the beast belonged to the governor, but even to his eye, it was an impressive creature.

“And the horse is already lathering,” Hatsukoi continued. “Can you take us across the river? I can pay you.”

Now, the fisherman had several boats at his disposal, but one look at Hatsukoi’s desperate face and the beauty of Tu Fang’s horse, and he was already corrupted.

“I have no boat to carry you both,” he lied. “But I will take you first, boy, and return to fetch your horse.”

Hatsukoi considered this – and at the same time, the fisherman thought of the pretty price the steed would likely fetch him on the next market day. “Much more than the fish,” he thought.

And Hatsukoi was watching him. “Yes,” he said at last. “Take me first.”

They went down to the riverbank, where a boat was tied to a wooden post. Hatsukoi jumped in, and with a long pole, the fisherman got underway. All through the journey, the fisherman’s eyes were misty with the dream of the money he could get from selling the horse that was not his. Soon, they were out of sight of the fisherman’s hut, and not long after, they reached the village.

As soon as Hatsukoi alighted, the fisherman pushed the boat away from the pier. “You need not wait for my return, lad,” he said with a sly smile. “The horse will find a new home with me.” And he laughed as he rowed back to his home, alone and against the strong current, which troubled him little now that he had the horse for his own.

It was after dark when he finally returned – and the angry hunters of Tu Fang were waiting for him there, just as Hatsukoi knew they would be. The hunter who had chased the boy found the abandoned horse by the river and returned to the castle with the news; the governor and his half-brother immediately set off in pursuit, but all they caught was one fisherman, guilty only of his own deceit and greed.

Meanwhile, Hatsukoi, having slipped straight through the village, went home, rejoicing in his luck. Gold coins jangled pleasantly in his pocket, and the thought settled in his head that it was not difficult to trick people who gave in to their vices. “It is a noble calling, then, to relieve such people of their possessions,” so decided Hatsukoi.